The Superiority of the Antagonist

Spoiler Warning: Mild spoilers for several franchises follow. They include The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Star Wars (prequel and original trilogies), the Hunger Games, and the Matrix.

Categorizing Plot By Beginning State and By End State

In school, I was taught there are three types of conflict our protagonist will face: with another person, with nature, or with him- or herself. The type of conflict I’ve always found most compelling is person-versus-person, a contest between two wills or a battle between two opposing powers.

For that type of conflict we can classify stories into two categories based on how they begin. In a world of order for which the normal state is “good” for the protagonist, conflict happens when a protagonist is challenged by an antagonist. Alternatively, the antagonist is challenged by the protagonist in a world of oppression for which the normal state is “bad” for the protagonist. But for both scenarios, the story usually goes from a normal state to conflict to triumph and back to a normal state; more or less following the plot structure diagrams we’ve all become accustomed to.

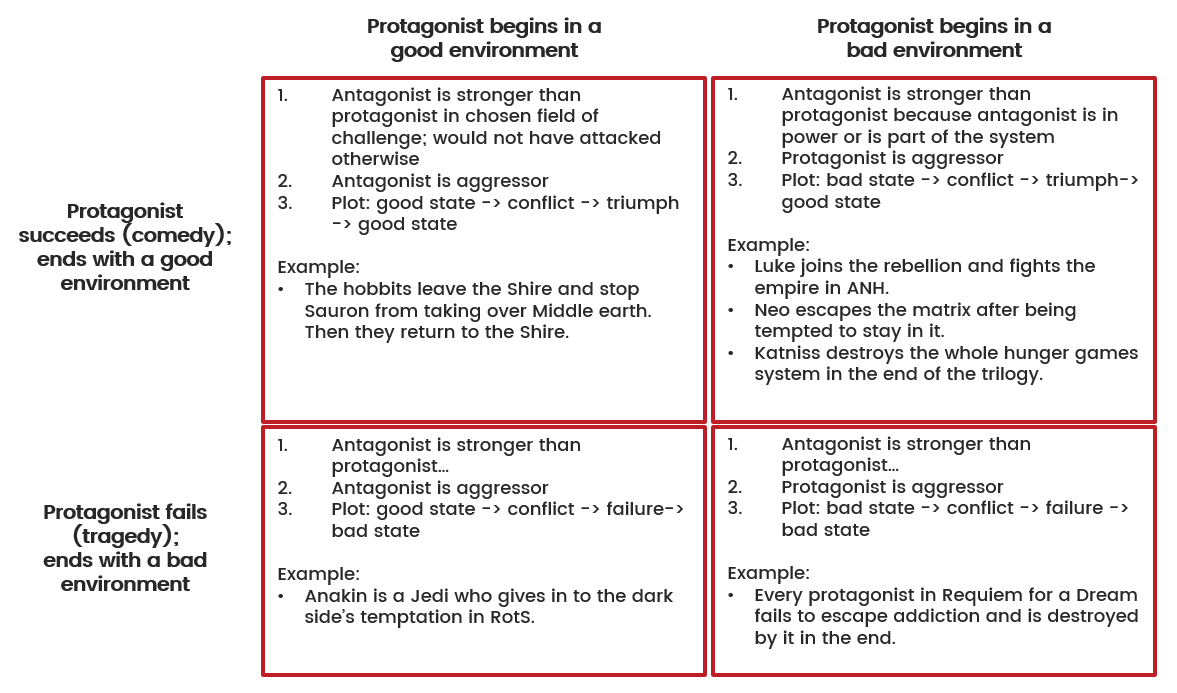

Of course, the protagonist doesn’t always succeed (a comedy in the Shakespearean sense), and may end in failure (a tragedy). This means we have a second way of categorizing a story; not only in how the story begins but in how it ends. Having two ways of categorizing a plot (beginning and end), each of these having two options (good and bad), we are left with four possibilities:

(1) protagonist begins in a bad situation, and ends in a good situation;

(2) begins in good, ends in good;

(3) begins in good, ends in bad; and

(4) begins in bad, ends in bad.

In a table it would look a bit like this:

Because life is improved by unnecessary tables.

When dividing stories into these four subcategories, the antagonist has to be the stronger force than the protagonist every time. The antagonist is obviously stronger in the bottom row (which ends in tragedy) because the protagonist fails to overcome him in the end. But even if there is a happy ending, the antagonist is the stronger. In the left column (starting environment is good for the protagonist), the antagonist challenges the protagonist because the antagonist is superior in whatever realm the he chooses the challenge, whether it be physical strength, political strength, or emotional sway. In the right column (starting environment is bad), the antagonist is stronger by default because the antagonist is usually part of the world or system which suppresses the protagonist.

The Roll (heh, heh) of Chance in Plot

Here’s a short but important detour. When a plot centers on a person versus person conflict, chance often waters down the story. If chance resolves the conflict, it renders the protagonist weak at best and unnecessary at worst. For me personally, chance may oppose the protagonist up until around the midpoint of the story. This isn’t some law written in stone, it’s more of a gut feeling I have.

If chance opposes our protagonist throughout, say the second act of a three act story, or even into the climax, it weakens the antagonist by making him lucky. Similarly, if chance aids the protagonist, it weakens the protagonist because now he is the lucky one. Characters are more compelling if they aren’t lucky as much as they are resilient. Now that the pesky topic of chance is out of the way, let’s talk about the antagonist.

The Role of the Antagonist

But it’s not enough that the antagonist is superior to the protagonist. The most effective villain or antagonist must test or attack the protagonist’s most dearly-held value. The protagonist must be challenged or tempted or attacked at his or her core. For example: The Joker continually challenges Batman’s stance to not kill, since Batman knows that the Joker will inevitably break out of Arkham and kill again. Similarly, Darth Sidious tempts Anakin (successfully) with saving what he holds most dear: his wife; which in itself is a betrayal of the Jedi order. The Devil tempts Eve (and then Adam) not with vice since they’re not inherently bad (yet), but tempts them with virtue. The list goes on.

While I stated earlier that we would focus on person-versus-person conflict, I have one little addition to make. Often when a good antagonist challenges the protagonist at his or her core, they may turn what has hitherto been an external conflict into an internal conflict. So, it seems that the pinnacle of person-vs-person conflict includes a bit of person-vs-self sprinkled over top of it all. The climax of Return of the Jedi is as much about the conflict between Luke and the two Sith, Vader and Palpatine, as much as it is a conflict inside of himself between the dark and light sides of the force. Even Frodo succumbs to internal conflict in the end of Return of the King. What’s up with all these Returns?

The Eventual and Unlikely Triumph of the Protagonist

How then does the protagonist overcome the stronger antagonist in the stories that end positively? If it’s obvious that the protagonist will win, because he is stronger than the antagonist in all conceivable ways, the story would be very short and uninteresting; in other words you have the wrong protagonist. Underdog stories are enjoyable because the protagonist wins even though he or she is weaker. It would be a waste of the reader/viewer/player’s time to tell a story that could be summed up by “the stronger character won.” We see this unfold in the real world all the time, and do not need to turn to entertainment to experience this.

I’m convinced that in whatever the field of challenge the antagonist is superior in, the protagonist must be stronger in another field or in another aspect. This field or aspect is morally superior or more valuable in some other way than the ideal chosen by the antagonist. It is morally superior in the protagonist’s eyes, similarly to how above “good” and “bad” mean “good for the protagonist” and “bad for the protagonist.” For example: Voldemort is the most powerful death eater in existence; but it is love again and again that protects Harry and defeats Voldemort in the end. Voldemort cannot defeat Harry because he refuses to understand the potency of love, but instead loves power. The villain chooses his field in which he is superior: strength in magic (or seduction, or physical strength, etc.), but is overcome by the protagonist who is superior in the superior ideal: love and self-sacrifice (or chastity, or friendship, etc.).

Moral Superiority in Stories for a Post-Modern Society

In our postmodern society many traditional values are challenged. Some of us even doubt that there is an absolute “measuring stick” to which moral superiority and inferiority can be measured with at all. But morality as absolute or relative is not up for discussion here. Here I am only interested in how values compare relative to each other.

Modern thought has popularized the anti-hero who embodies some of the traditionally less valuable ideals like ambition or wealth or pleasure. This only means that the antagonist has to choose a field of challenge that is less valuable than those ideals our anti-hero holds dear. Our modernist mind shrinks away from absolute morality but will still find sins like prejudice, hatred, dishonesty, and bigotry to be absolutely wrong, absolutely all the time. For example: killing complying, unarmed soldiers is murder by most standards. Yet when the Inglorious Basterds do it, it’s acceptable because they’re killing unarmed soldiers (and even a few civilians) who are part of a government that killed unarmed civilians by the millions. For most of us, valuing revenge is comparatively less bad than valuing racial purity to the point of committing genocide. The murder of unarmed soldiers and civilians bothers me (personally I think wrong is wrong), but I get it.

I can’t just rail against anti-heroes. I love A-New-Hope-era Han Solo (who shoots first) as much as the next guy. The strength of using anti-heroes is that we, the audience, can relate to them more than to perfect heroes since we ourselves don’t live up to all virtues, all the time. Also, it’s fun to be bad. I get that. But the biggest downside to the use of anti-heroes is their prevalence in today’s entertainment. They are all the rage right now, and like good food someone has eaten too much of, somewhat off-putting because of their overuse. Anti-heroes are a delight in appropriate doses. In the end they follow the general trend like all heroes: they are weaker than the antagonists initially but possess some virtue or hold to some ideal that is superior to the virtue chosen by the antagonist.

Takeaway

I like a good story. I like a good struggle because it encourages me to struggle in life and not to give up when things get hard. For that I need a good protagonist, but protagonists can only show their strength as much as the antagonists challanges them. Thank goodness in life I rarely face conflict that is person-versus-person. My biggest enemy seems to be comfort. In that respect, we who live in an age of consumerism and convenience are faced mostly with the person-versus-self conflict. And yet, our own story is better when we rise against those inner enemies and meet them head on. That means progress in the face of exhaustion, love for a neighbor that isn’t lovely, or self-discipline when comfort is so much easier. Like I said, I like a good story.

I probably did not write anything revolutionary here. The more I google about this subject the more I realize it’s common knowledge that the stronger the antagonist is, the better the story. I’m just sitting at my little desk in the corner of my office, asking myself what makes a bad guy good, and a good guy gooder. Thanks for reading. Let me hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Peace.

More Stuff to Check Out

Much has been written and said regarding how the Joker is a particularly great antagonist. I enjoyed watching Lessons from the Screenplay’s “The Dark Knight — Creating the Ultimate Antagonist.”

Also, if storytelling and plots interest you (why else have you read this far?), Robert McKee’s Story: Style, Structure, Substance, and the Principles of Screenwriting (introduced to me by the LftS channel above) is an excellent book. I enjoyed listening to it quite a bit.

Recent Comments